How Teacher Salaries Became a Political Weapon

The funding formulas, systemic inequity, and structural nonsense keeping teachers underpaid.

In a gif:

We entrust teachers with our children and the country’s future, and then hand them salaries that barely cover rent, student loans, groceries, travel, or glue sticks (which yes, they are somehow still expected to buy themselves).

But the deeper you go, the clearer it becomes: this isn’t just a pay issue. It’s a weaponized political issue.

So today, we’re diving into the complicated world of education funding, teacher pay, and the structural nonsense that keeps most educators broke and burned out.

The Pay Paradox

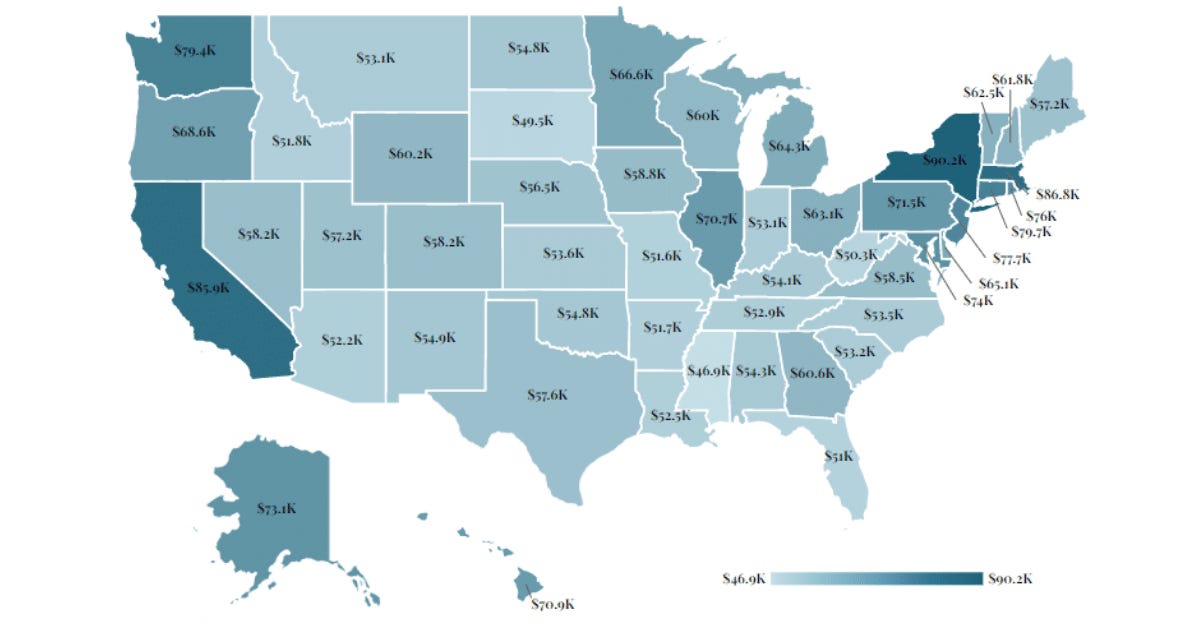

Teaching is one of the only professions that requires multiple degrees and still qualifies you for food stamps in some states. The national average teacher salary in 2023 was around $66,000, but that number hides a thousand inequities.

In Mississippi, you might start at $41K and max out at $50K. In New York, maybe you reach $100K after 20+ years - but good luck affording groceries in Brooklyn.

Even those salary numbers doesn’t tell the full story. When you compare teacher pay to each state’s cost of living index, the gaps get even more painful.

Teachers in high-cost states like California, New York, and Hawaii are often functionally living below the poverty line - especially in their early years, despite their education and credentials.

And don’t forget: when you adjust for inflation, teacher pay has actually declined. In 2022, real teacher salaries were 4% lower than in 2010. The vibes are… disrespectful.

Let me get personal for a second: I taught the longest in Los Angeles County, one of the most expensive places in the country to live and work. During my first year teaching, I was placed at a school in a wealthy area on the Westside of L.A. And yet, I lived in a windowless studio apartment that cost $1,300 a month, and I had to commute an hour and a half each way because I couldn’t afford to live anywhere near the school or the community I served.

I was a full-time teacher, with a college degree and a fifth-year credentialing program under my belt, and I was barely scraping by.

My situation was certainly not unique. We can break it down by the numbers.

In 2025, the HUD median family income in L.A. County is $106,600. To qualify as low income, a single person has to make less than $84,850. The very low-income level is $53,000, and the extremely low-income level is $31,850.

Now, compare that to the LAUSD pay scale. If you have a bachelors degree and went on to earn your teaching credential, you’re likely starting at “Pay Scale Group 23” and “Pay Scale Level” 1. That’s $70,206.

Even if you have a master’s degree and a doctorate, you’re not clearing that “low-income”cutoff for years. And to make it extra fun: a teacher with both a master's degree and a doctorate only gets credit for one. You don’t get both pay bumps.

Although teachers are highly educated professionals, we don’t pay them like it.

Where’s the Money?

A lot of people assume the federal government foots the bill for public schools, but in reality, the U.S. Department of Education only provides about 8–10% of K–12 funding. And that money is mostly earmarked for supporting our most vulnerable students. The remaining 90–92% comes from state and local sources, with property taxes doing the heavy lifting.

If your district sits on top of high-value real estate, you’ve probably got well-funded schools. If not? Welp…better luck next ballot measure, I guess.

School budgets also cover a lot list of costs in addition to teacher pay. Things like transportation, utilities, cafeteria workers, and administrative roles.

But, for some reason by the time teacher salaries come up, it’s: “Sorry, the money’s already spoken for.”

Salaries: The Budget Leftovers

Most teacher salaries follow a “steps and lanes” structure, meaning you move up with years of experience and degrees. But it can take decades to reach a livable wage, and many teachers get stuck on frozen salary steps during budget crises.

The jump from my second year salary to my third year salary was literally $114. Like…yeehaw. Meanwhile, my friends working in corporate were sad that their annual raise was only 4% - even though their yearly bonus was only 7%.

For those who don’t know (because I didn’t): In the corporate world, employees typically get 3–5% annual raises, and bonuses can range from 5–25% of their salary. You’d think that because Republicans are so eager to run schools like businesses, they’d want to compensate teachers like corporate professionals.

Alas - no.

After the 2008 recession, over 300,000 education jobs were slashed, and many districts never recovered. So today’s new teachers are basically entering the field and those old wounds are baked into the budget.

And the consequence of that is - when money gets tight, many districts start avoiding experienced teachers because they cost too much. This is a little bit of inside info, because it’s not something districts come out and say.

There’s a growing number of experienced, highly qualified teachers who apply for jobs and get ghosted while newer, cheaper hires with far less experience walk right in. Anecdotally, many veteran teachers say they’ve been passed over simply because their place on the salary schedule makes them "too expensive." I’ve seen friends let go mid-year for this very reason.

That means the system actively disincentivizes loyalty, training, and growth. Educators with years of classroom experience, advanced degrees, and additional certifications find themselves pushed out or never hired at all.

Follow the Money

If you’re wondering where school funding actually comes from, the answer is…complicated. It’s a tangled mess of formulas, acronyms, and people in suits who make budget decisions from very far away (often with no teaching experience).

We’ve already talked about federal money in this Stack.

It makes up less than 10% of most school budgets and these funds are distributed via “categorical grants,” meaning they have to go to funding specific things like Title I (for low-income students), IDEA (for students with disabilities), and academic or enrichment supports.

States with larger populations of low-income students across large swaths of rural areas tend to receive a larger share of federal education funding.

Translation: red states take the most.

State money makes up around 47% of K-12 school budgets, but it varies wildly. Most states use a school funding formula that divvies up money based on things like student enrollment, poverty rates, English learner populations, and special education needs.

But the thing is - state funding formulas are crafted, revised, and enforced by politicians.

In some states, governors use education funding like a reward system. In other words: more money for districts that fall in line, less for those that push back.

It’s not always about students’ needs - it’s often about messaging. Want to pass a conservative "pArEnTaL rIgHtS" bill or ban DEIA programs? Here’s a lil money.

Speak out in support of LGBTQIA+ students or inclusive curriculum? Bye bye federal funding, see you in court, good luck.

Some states even use competitive grant programs instead of guaranteed funding. If you’ve never worked in the grant-writing world, this means your school needs to hire a whole person whose job it is to beg the government for money that you may or may not be awarded.

And then there’s the political pressure to lower state taxes. When states cut income or corporate taxes, they often offset the revenue loss by underfunding schools, leaving districts to fill the gap. (Spoiler alert: they usually can’t.)

Local money, mostly from property taxes, makes up about 45% of schools’ funding - which is where things get spicy. And by spicy, I mean segregated.

This is what I spent my first semester of graduate school researching, so I get a little bonkers over it.

Because property taxes are tied to real estate values, schools in wealthier neighborhoods automatically generate more local funding, regardless of what their students need.

This inequity even exists within school districts themselves. Two schools in the same district, a couple of miles apart, can look and feel completely different.

And this is completely on purpose, by the way. Public education’s funding system was built on the same foundations as redlining and housing discrimination.

In the mid-20th century, federal housing policies explicitly segregated neighborhoods by race, and local governments followed suit by tying school funding to property taxes. That created a self-fulfilling prophecy: white, wealthier communities were allowed to accumulate property wealth (and therefore education dollars) while Black and Brown communities were systematically disinvested in.

And let’s be real: this is “separate but equal” 2.0. Just with a Homeowners’ Association and probably a fundraising gala or two.

When courts mandated racial integration, white families fled to the suburbs and took their tax dollars with them. Today, some communities still vote down local education bonds or parcel taxes because they believe their money shouldn’t go to “other” kids. Yuck!

Side note: A lot of right-wingers are simply so racist, they forget rural schools also struggle with low property values and fewer local resources. In the 2021–2022 school year, about 63% of traditional public schools and 62% of public charter schools qualified for Title I.

That’s a majority of the country!

So Who’s Calling the Shots?

1. Governors

They propose the education budget and can push specific policies. Governors often campaign on education plans (but they still need legislative approval.)

2. State Legislatures

They set the state’s education budget and determine the funding formula. These formulas are based on student demographics (like poverty rates, English learners, or disability status), but some are decades old and don’t reflect current needs. They can also quietly bake in inequity depending on how "local wealth" is factored in.

3. State Departments of Education

They distribute money based on the legislature’s formula, monitor compliance, and they’re supposed to help districts manage resources. But between 2008 and 2018, states collectively disinvested nearly $600 billion from public schools.

That’s with federal oversight. Imagine the chaos without it.

4. Local Governments & School Boards

Your locally elected school board determines how much goes toward salaries, facilities, curriculum, and staff. But they operate within the constraints of the money they receive. They also approve parcel taxes and education bonds.

In wealthy areas, those pass easily. In lower-income areas? Not so much.

5. The Federal Government

Their slice of the funding pie is small but so critical. Federal dollars fund everything from Title I and IDEA to college access programs like Pell Grants. This money and the oversight it comes with is essential to making schools anywhere close to equitable.

6. The Courts

A bunch of school funding systems have been challenged in court as unconstitutional. Courts have ordered states (like Pennsylvania) to reform funding formulas.

Time and time again, legal rulings have forced equity where politics wouldn’t.

Underpaid + Overworked = Teacher Exodus

Teachers are underpaid and expected to function as a social worker, nurse, tech support, grief counselor, and substitute parent every single day.

Support staff are getting cut left and right, and teachers have to pick up the slack. One minute you’re teaching long division, the next you’re managing a full-blown mental health crisis in the hallway because the school doesn’t have a counselor on staff.

The burnout is not only real, but measurable. In 2023, 44% of teachers said they were thinking about leaving within two years. And it’s not because they don’t “wAnT tO wOrK.” It’s because, in many cases, the work has become impossible.

While teachers are burning out and sharing Venmo links to fund classroom supplies, testing companies like Pearson are cashing billion-dollar checks.

There’s a whole industry profiting off public schools.

Even platforms like Teachers Pay Teachers rely on unpaid labor.

And here’s the kicker: when districts do get an unexpected influx of cash from a legal settlement, federal grant, or state-level reform, what they do with that money tells you everything.

Again, I Ask: Where’s the Money?

According to researchers Paul Peterson and Carlos Lastra-Anadón, how school districts respond to unanticipated revenue depends on their state’s labor laws. In states that don’t require collective bargaining, districts tend to hire more staff. In states with duty-to-bargain laws, districts are more likely to increase teacher salaries (which, based on achievement data, may actually be the smarter move.)

In states where hiring more staff didn’t show a meaningful boost in student outcomes, raising teacher pay was a more effective and sensible use of funds.

But the real scandal isn’t whether districts hire another librarian or raise teacher salaries…it’s that they’re almost never given enough money to do both.

Frankly, not all pay raise policies are created equal.

In states like Texas and Florida, politicians stick teacher salary increases inside of bills about gutting unions, dismantling tenure protections, and introducing school voucher schemes. It’s honestly gross.

And while some policy proposals at the federal level sound promising, experts caution that a one-size-fits-all fix won't solve a highly localized, complex problem. Instead, the experts suggest reforms like targeted bonuses, incentives for quality teaching or paying all teachers at the master’s degree rate without forcing them into debt for another diploma.

Some other things we need to do are:

Fully fund Title I and IDEA so schools serving low-income students and students with disabilities aren’t scraping by.

When IDEA was signed, Congress promised to cover 40% of the costs associated with educating our disabled youth. They have never gotten close. This year, they covered only 12% of the costs.

Break up with property taxes as the main funding stream.

Explore a federal teacher salary floor.

Add back school counselors, nurses, and librarians.

Protect teachers' right to unionize and collectively bargain for better working conditions.

We need to stop treating schools like afterthoughts and start treating them like the actual infrastructure of democracy that they are. And, if you recall this Stack, politicians know they are.

Basically, We Know Better. We Need to Do Better.

Teacher working conditions are student learning conditions.

When we underpay teachers, we’re saying that we’re cool with a society where children’s outcomes are determined by zip codes and political agendas.

And if your state rep tells you there’s no money? Ask them how much your district is spending on standardized testing this year! 😇

Because it turns out the answer to “why don’t we pay teachers more?” isn’t that we can’t. It’s that we don’t.

And when we do spend on education, it’s often on things that don’t actually help kids learn or teachers stay.

We’ve reached a fork in the road. Policymakers can either use this moment to build a better, more equitable education system, or we can watch the Trump administration dismantle the public schools that serve 90% of kids in this country.

Teachers are essential. It’s time to fund them like it.

Thank you for reading! I’ll see you next time 💕

- Frazz